Sunset from Swans Island, Maine. Shot with digital internegative method, Kodak Ektar/Phase One IQ3 100MP Trichromatic. More info in article!

Hi friends!

It's been a few weeks since I last wrote you. Lots has happened, and I've got a lot to share.

First things first, I've been writing a ton for work, helping our marketing team as a technical writer, and quite honestly that's left me a bit burned out on the writing.

Phase One, the camera system company that builds the super high-resolution systems we use throughout our company, just announced a brand new camera system that's probably the most radical product they've announced in the past five years or so, so things are super exciting around the office, but it's all hands on deck all the time!

We finally got a couple of prototypes in-house this past week:

If you're interested in more information about that, you can check it out here, or just ask me. Fair warning, I'll talk your ear off.

Technical writing has made use of a lot of the same skills that I've tried to hone here - making the technical aspects of photography accessible to a broad audience, and in doing so hopefully give them a greater appreciation of the magic of optics, photonics, and image processing.

If you're interested in looking at one of those articles I wrote, you can check one out here. They're intended for a more specialized audience and as such, are a bit more technical and specific to the idea of why megapixels matter, and why a camera might be worth $50,000+. So if you're not already familiar with high resolution DSLRs or medium format, it might not be terribly interesting, but I'm always looking for feedback.

I can say that I've been very proud of the work though, and have gotten several nice messages from company clients, some of whom I've never even met in person! Here's one:

"Hi Arnab,

Well done. I appreciated some of the geometry prior to reading your in-depth plunge, but learned much more and, most importantly, learned how to better present the facts and issues to other club photographers.

Thanks again for pulling all the details into such a well written paper."

It feels great to communicate science and engineering to others, and in this particular case, extend that understanding as they share it further.

But enough about that nerd stuff that doesn't apply to you. Let's explore something super sciency, that almost every one of you has attempted at some point - sunset photos.

Shooting Sunsets

Everyone's done it at least once. Perhaps you're out on a beautiful evening in the country, or on the beach, or even on a rooftop or by the water in the city. The sun starts to get low on the horizon, the sky starts to change colors, and the sunset commands your attention.

So you pull out your phone, and take some pictures. Maybe you even try and take a photo of a friend with the sunset in the background. But everything you shoot either comes out too bright or too dark, and the colors don't look as vivid as they do in real life.

Not to worry, Instagram can save the day. Just add some clarity, pump up the HDR, and blast that saturation and we can turn the photo on the left into the one on the right:

Looks great, right?

Right?

Ok, so we’ve gone too far. But our phones are so good at taking photos of pretty much everything. Why is it so hard to take good sunset photos?

The Highlight of the Evening

First things first - the sun is bright. Really bright.

And when it's setting on the horizon, everything you see in front of it is backlit unless there are other lights in the frame with brightness on the same order of magnitude.

This typically doesn’t happen, but if you happen to have a portable light that is as bright as the sun, please notify me so I can steal it and sell it to every energy company on earth.

Anyways, managing a super bright sky or a really dark foreground isn't terribly difficult for our eyes - when we look at the skyline and then back at the foreground, our brain simply adjusts our optics and switches image processing methods.

While we won’t go into it in detail here, that latter bit is actually very complicated and the amount of work that our brain does behind the scenes is mind-blowing (no pun intended). But we're so used to it happening passively, that we don't think twice about it (no pun intended).

So we can handle the foreground, and we can handle the background. The problem arises when we try to capture both in the same image. The dynamic range in the image - the difference between the brightest point in the image, and the darkest point in the image - is crazy high. The sun is over 1 million times brighter than the darkest parts of the foreground in a sunset, and neither our camera phones (nor even most expensive cameras) can handle highlights that bright and shadows that deep at the same time.

So how do get both in one shot? Well, there’s one super simple answer!

The Answer

You can't.

But I want to!

Oh fine. We’ll try and find a workaround.

With a camera with a very limited dynamic range, like a cell phone camera, we're going to either have to choose to save the sky and sacrifice detail in the shadows, or save the foreground for and sacrifice details in the highlights in our photo.

It's a decision of personal taste, and contextual as well. If you're looking at a landscape or cityscape, saving the sky provides great color, range, and a nice silhouette. But if you're taking a photo of a friend with the sunset in the background, you can't get away with that. I've tried, they get mad.

To try and get both in one image, you have to lower the dynamic range by making the shadows brighter, or by bringing down the highlights.

But you can't turn down the sun.

I think.

If you can, again, let's link up and take over the energy sector.

Under normal circumstances though, you have to find a way to bring up the shadows. This is where HDR comes in.

HDR can refer to a wide variety of things, but in this case, we’re talking about taking multiple frames at different brightness levels, and blending them together.

Chances are if you're using a really nice phone, the newest sensor technology can capture all of the frames at the same time on one sensor. Stacked sensor CMOS technology is crazy. Ask me about it sometime.

This works really well, then, and is pretty much just limited by how good your cameras are and how good your blending is.

These days, both are quite good, so HDR extends the dynamic range of a lot of cell phone cameras in a lot of conditions. Unfortunately, noise is the other factor that can cut into dynamic range, and small sensors tend to have much more noise (this is why your shadows can look grainy or have weird colors), so this method only works up to a point.

Additionally, in situations like sunsets, using three frames (a common number) to capture everything in the scene would require the exposures to be so far apart that blending them would look unrealistic and create erroneous tones, so phones will typically have a limit to how wide they allow HDR algorithms to spread.

There are other ways to get HDR-like effects though, even if you don’t have a phone that has true HDR built-in.

You can fix that in Photoshop, right?

Apps like Instagram (and for that matter, Capture One, Photoshop, and Lightroom) allow you to adjust the dynamic range of an image after it’s taken. But when you use the shadow and highlight tools when you're editing an image, you're pushing and pulling data around, which makes images start to fall apart unless they’re extremely data-rich, like a camera RAW file.

In phone images (or even some higher end camera images), this leads to the infamous “halo effect” we've all seen, among other things. (If you don’t know what I mean, I’ll point this out in an image in a minute.)

So using built-in HDR in your camera app is almost always better than adjusting the shadows in an app.

And the same goes for you DSLR and mirrorless photographers - getting it right in camera is always better than fixing something in post-production software like Photoshop.

But the best solution from a technical standpoint?

Use flash. It genuinely brightens your shadows without digital trickery, decreasing the dynamic range of the scene.

But despite being a perfect engineering solution, it’s often a terrible artistic solution.

So our phone can't handle all that dynamic range. What happens when we get a better camera?

Better Cameras Make Better Pictures

Despite the much maligned and mostly untrue statement above, sometimes better cameras do make for better pictures.

On a DSLR, mirrorless, or medium format camera, you can shoot raw images, which are more malleable and maximize dynamic range in a way that lets you push and pull data much further before the file falls apart. They also shoot in higher resolution and greater precision in digitizing brightness values, making transitions from shadows to highlights much smoother.

So the best of these cameras don't have to shoot multiple frames, because they can capture that wide dynamic range in one shot with their specialized sensors. And there are a lot of techniques you can use to make this work better (polarizers, graduated ND filters, bracketing, foreground strobes, etc.) but let's leave all that aside.

Realistically, with a raw image from the new $51,000 Phase One XF IQ4 150MP (isn't that a mouthful?!), I can take one shot of a sunset and modify it to bring my shadows up, and my highlights down, and still have a good looking foreground and sky.

But it's going to look all wrong to our eyes! We know that there are certain relative intensities of light and darkness, and if we were actually able to fit a scene as wide in dynamic range as a sunset into a particular medium, it would just look wrong.

Our eyes can’t capture the entirety of a sunset all at once, and that fits into our perception of the experience of a sunset. Show me a sunset image with full foreground detail and sky detail and it won’t look real, or even good.

So the real secret is that a good sunset image lies in understanding that you’ll lose some detail, and carefully deciding where to place it.

So without further ado, let’s look at one of my sunset images from my recent trip to Maine:

Oh whoops. Let’s try that again:

There we go. Click for full resolution!

This image was shot as a negative on film and scanned on the DT Atom, which uses a Phase One 100MP camera to image the film. I processed it in Capture One to make a positive image!

This is a process that I use for a lot of my serious images now, and there are a lot of benefits and downsides to it. I call it the digital internegative process, and I think it grants the patient user extraordinary results if they’re willing to spend days working on their images.

As you can see, I elected to keep they sky all within my dynamic range, except for, of course, the sun, which is “clipped,” or “blown out” - different terms for describing a piece of the image that goes beyond our dynamic range. There is also a bit of that “halo” effect around the border of the leftmost tree. That’s more of an artifact of the internegative process and the fact that this is a low resolution JPG, but I do address this in Photoshop and it’s certainly has a mild similarity to the halo artifacts on over HDR’d images.

While I could image the sun in such a way that it wasn’t completely blown out, everything else in the image would be pitch black, and there wouldn’t even be any detail in the sun to draw out anyway.

That’s one of the key considerations when working around dynamic range. I can confidently leave the sun outside of my dynamic range because there’s no image content or information in it that I care about in rendering my image. The same goes for deep shadows, as long as there’s nothing in them that I want to show to my audience. But in this case, I do want to keep that shadow detail where I can!

So how do I shoot my image to make sure I get this right?

One straightforward method of shooting in a high-dynamic range situation is to choose what you absolutely want to keep in your image, and center your exposure around that. The sky and particularly the color in the lower regions of it are where I chose to spend a great deal of my dynamic range, so that’s what I centered my exposure around here. I was alright with the trees and rocks losing some detail as they’d create a nice silhouette.

Now all of that is true of digital photography, but by using film to capture the initial image, I can actually cram a ton more content into my highlights than I can on any digital medium. So this image is severely overexposed by digital standards, but thanks to the film, I don’t lose any highlight detail, and that leaves me a ton of nice shadow detail as well. When I scan the film, I can keep all that great highlight detail, and I can draw out all of the shadow detail associated with high-quality digital cameras. It’s the best of both worlds.

The shadow detail was really important to me in this image. While a hard silhouette of the rocks and trees in the foreground would look fine, but the texture and detail in the rocks and branches, and the orange-gold glow on the cliff face yield a three-dimensionality to the image that would otherwise look flat.

Also, having seen a lot of incredibly talented landscape photographers, I’ve learned that the shadows carry an inexplicably intimate subplot in the best images, taking a monument that may have been photographed millions of times and adding depth and emotion to it. Oftentimes this can be done with clouds as well, and so stormy days can be more dramatic than clear ones.

But I really just love the look of the rocks, glowing, and fading in and out of shadow. They’re like a soft melody that forces you to lean in and listen carefully. Take a look at the image in full resolution here.

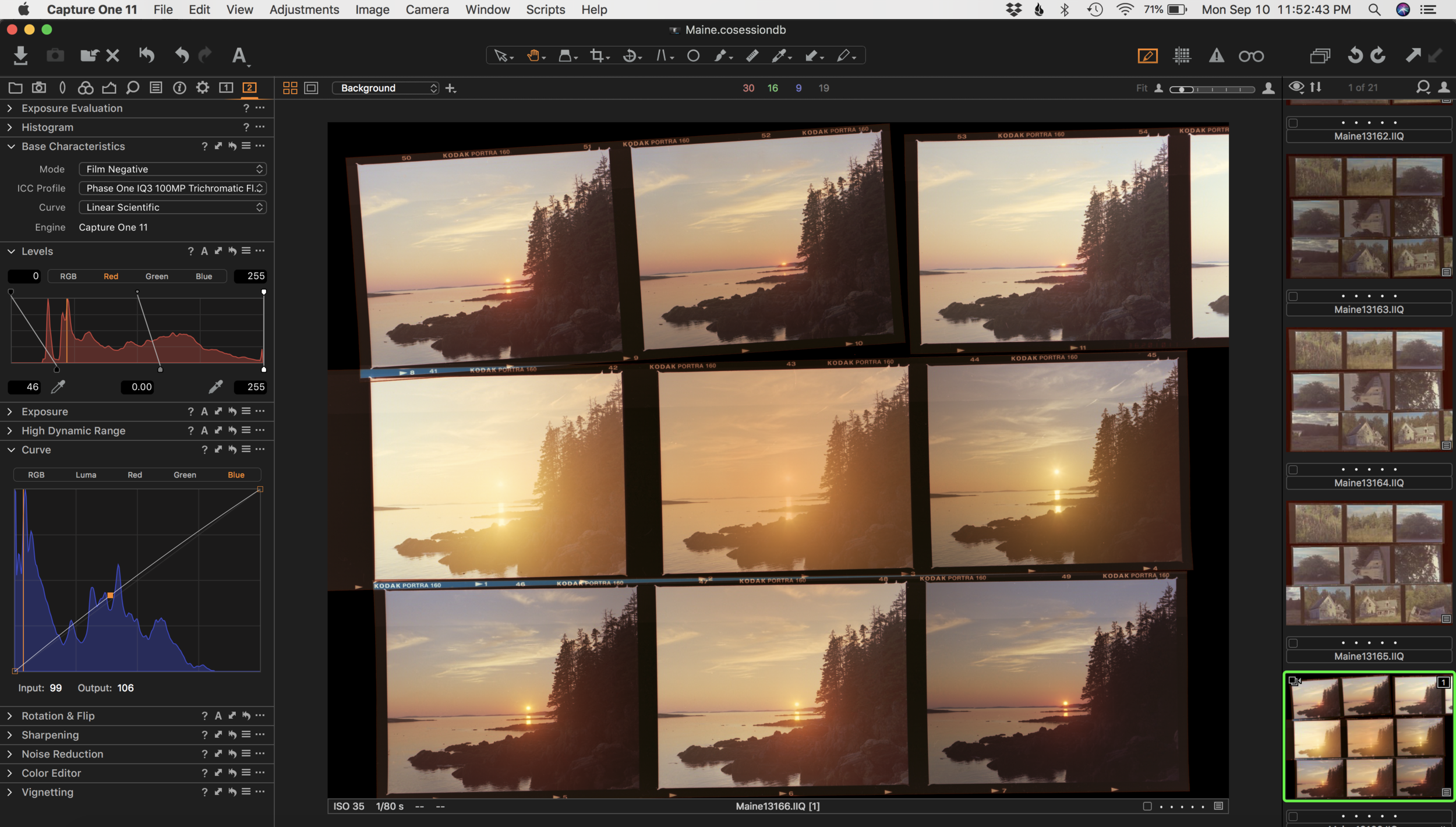

The last note I’ll make is that there are elements of art and science, but there are also elements of practicality and resilience. Behind every good sunset photo, there are at least a dozen not-so-good ones, and personally I’ve taken hundreds. Here are just a few of the not-so-great ones from that shoot alone:

So to wrap up, it’s been a long, long month, but a good one. I hope you enjoyed hearing about what I’ve been up to, and I’m looking forward to catching up with you all too!

Much love,

Arnab Chatterjee